Specificity of Transcription Factor Binding Sites Matrix Families

Abstract

Understanding cistron expression will require agreement where regulatory factors bind genomic DNA. The frequently used sequence-based motifs of protein-Dna bounden are non predictive, since a genome contains many more binding sites than are really spring and transcription factors of the aforementioned family share similar DNA-binding motifs. Traditionally, these motifs just depict sequence but fail DNA shape. Since shape may contribute non-linearly and combinational to binding, machine learning approaches ought to exist able to ameliorate predict transcription factor binding. Here we evidence that a random woods machine learning approach, which incorporates the 3D-shape of Deoxyribonucleic acid, enhances binding prediction for all 216 tested Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factors and improves the resolution of differential binding past transcription factor family unit members which share the same bounden motif. We observed that DNA shape features were individually weighted for each transcription factor, fifty-fifty if they shared the same binding sequence.

Introduction

Changes in cistron expression during evolution and invoked by environmental perturbations are critical to organismal function and these changes are influenced by DNA-binding transcription factors (TFs). Arabidopsis thaliana encodes 1533 DNA-binding TFs1 many of which occur in protein families of a few to over a hundred members2. Gene expression of a detail factor is a complex read-out based on the presence of TFs and their spacing on the DNA, chromatin condition, histone marks and presence of co-activators or repressors. Improving the agreement of those regulatory relations and pathways is necessary to tackle current agricultural challenges3. Hundreds of sequence motifs to which TFs bind have been characterised4,v, but currently it is impossible to look at a promoter and sympathize its regulatory syntax. Dna is a very constrained molecule since its phosphate sugar backbone runs antiparallel while its bases are paired and arranged in rungs on a helical ladder. However, despite the constraints, the exact position of each base of operations pair and each base of operations in a pair is influenced past its surrounding bases. The pairs can be tilted, shifted, slid, rolled, risen and twisted relative to each other (Fig. 1d;six,7). The bases in a pair can be buckled, sheared, stretched, twisted, opened and staggered (Fig. 1d;6). The width of the pocket-size groove is too influenced past the surrounding basesviii. This Deoxyribonucleic acid shape has been demonstrated to influence protein–Deoxyribonucleic acid binding, for instance, of the Drosophila Scr Hox Proteinviii,nine and the Southward. cerevisiae bHLH proteins Cbf1 and Tye710.

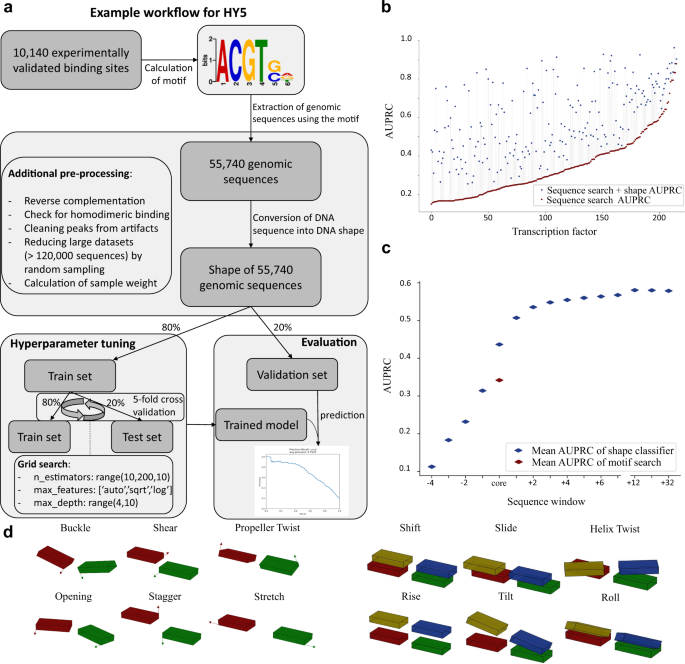

a Instance workflow illustrating the computational steps from publicly available data to trained models capable of predicting protein–Deoxyribonucleic acid binding affinity. b Performance of the random forest classifier using the border width (number of upstream and downstream bases) with the highest surface area under the precision recall curve (AUPRC) for each TF. c AUPRC for differing sequence widths. The width was increased upstream and downstream of the core motif sequence, respectively. d The different Deoxyribonucleic acid shape features which were considered to analyse TF specificity. A query tabular array was used for shape calculationsix.

Many members of a particular TF family bind the aforementioned motiffour. The A. thaliana genome contains 74 members of the WRKY TF family unit11 regulating diverse processes from trichome and seed development to roles in biotic and abiotic stresses12. All WRKYs analysed bind to a consensus motif, the W-box, which is characterised by the TTGAC pentamer followed by C or Tthirteen. TFs of the 133 member bHLH family demark DNA via basic amino acids at the N-terminal end of the bHLH domain and bind a variation of the motif CANNTG, frequently the so-called G-box CACGTG14. This G-box motif is also bound by many bZIP TFs whose core motif is ACGT, the key nucleotides of the Yard-box CACGTG15,16. Fleck-seq information clearly indicates that but a subset of potential bounden sites are indeed occupied at whatsoever given time in a particular tissue17,18,19. We hypothesised that DNA shape was a critical element for determining TF specificity within a TF family.

In amplified Deoxyribonucleic acid affinity purification sequencing (ampDAP-seq) experiments amplified DNA devoid of methylation marks is bound to an in vitro produced TF and sequenced. For motif detection in ampDAP-seq or ChIP-seq, the Dna sequences spring by the TF are mined by motif search algorithms such as MEME or MEME-ChIP, which identify overrepresented motifs amid the sequences20. For many TFs, biochemical experiments such as electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) have confirmed that the motif is necessary for bounden21,22,23. However, the comparing between the measured bounden events from DAP-seq data and the frequency of the derived motif in the genome indicates that during motif prediction information is lost (Fig. 1a). In our analysis, the identified binding motif occurrence is on average 14-fold college than the number of verified binding events (Supplementary Fig. 1). We hypothesised that binding specificity of a item TF is encoded in DNA shape. To decipher the predictive power of DNA shape regarding poly peptide binding, we trained a random woods model. This approach enables the detection of not-linear relationships between the shape of the bases and Dna-binding affinity. In addition, information technology allows the capture of possibly important combinatorial data of not-adjacent bases. We hypothesised that motorcar learned models trained on DNA shape inside and surrounding the bounden motif recover the lost data during motif detection and generally improve prediction for TF binding in A. thaliana. In this piece of work, we contribute to the understanding of poly peptide–DNA recognition and demonstrate that Deoxyribonucleic acid shape features enable a robust prediction of binding affinity regarding randomly generated motif containing sequences. In improver, we show that the models, trained on Deoxyribonucleic acid shape, improve the distinguishability of binding locations for TFs that share the same binding motif. Understanding TF binding equally a combination of motif sequence and motif shape brings us closer to predicting gene expression directly from sequence.

Results

DNA shape features explain large part of protein–DNA binding affinity

To generate the datasets necessary for training, examination, and validation, for each TF the sequence-based binding motif (henceforth chosen "core motif") was determined with MEME-ChIP using all ampDAP-seq peaks. Sometimes a motif is reported based on only the 600 peaks with the largest height4; we opted to capture all binding events. The genome was scanned with the motif generating two classes of events: motifs, which are non underneath a tiptop and hence not spring and motifs underneath a meridian which were bound. Peak height is taken every bit a proxy for analogousness. If a motif based on but the top 600 peaks was used, the number of sequence-only-based potential binding sites was increased (Supplementary Fig. 2) likely because those larger motifs reach the threshold for FIMO24-based extraction more hands compared to smaller motifs. A random forest conclusion tree (RF)-based regressor25 was trained for each TF on the raw binding information using the elevation height in ampDAP-seq equally a proxy for binding affinity afterward binding data was filtered for single motif occurrences. On average, 146,326 sequences, which contain the binding motif, were extracted to train the models. For the TF with the least corporeality of grooming data nosotros extracted 18,210 sequences, whereas the largest dataset for a TF independent 640,292 sequences. To ensure consequent 3D structure learning, the sequences were reverse complemented if the binding sequence was located on the reverse strand. Nosotros dissever the motif occurrences into a training and a validation gear up25 using the measured indicate value within the peak calling of the ampDAP-seq experiments as the numeric characterization. The training dataset was again separate into railroad train and examination gear up (ratio iv:i) while performing cross-validation. In addition, nosotros explored dissimilar ratios of train to examination gear up (iv:1, 3:1, ii:1 and 1:1) and observed no divergence in performance (Supplementary Fig. iii). This indicates that the size of the input dataset is sufficient for robust grooming.

In total, 216 individual models for 216 TFs were generated. In each case, the shape-based predictor outperformed the motif search, based on the area under the precision remember curve (AUPRC). AUPRC improved between 2.8% and 362.7%, with an average of 93.2% (Fig. 1b). 33 TFs accomplish AUPRC of more than 0.8 indicating that the motif plus shape information suffices for prediction (Fig. 1b). 101 TFs evidence medium AUPRC betwixt 0.five and 0.8. The remaining 82 TFs show improved AUPRC compared to motif alone just does non exceed 0.five (Fig. 1b). To investigate the influence of dimensionally reduced input features on model performance, all models were additionally trained after performing PCA on the shape features (Supplementary Fig. 4). The prediction performance was substantially lower when the models were trained on the dimensionally reduced features rather than the directly shape features. This ascertainment as well implies that the features are not considerably redundant.

Prediction of bounden improved for all TF families, all the same, some families increased in prediction precision more than than others (Supplementary Figs. 5 and six). We analysed whether this discrepancy could be explained by the dissimilar dataset sizes, which is the number of genomic sequences containing the motif (Supplementary Fig. seven). Indeed, we observed a slightly negative correlation between performance and dataset size with an R 2 of 0.154. Hence, on average the prediction functioning is slightly worse for TFs whose sequence motif is more abundant in the genome. An additional comparison between ampDAP-seq and Fleck-seq data was performed for five TFs, for which information of both experimental procedures were available (Supplementary Fig. 8). We observed that ampDAP-seq outperformed ChIP-seq for each TF with an average of 98.6% higher AUPRC. This observation is in line with our expectation, equally ampDAP-seq identifies bounden events independent from weather in the prison cell and uses unmethylated naked DNA for the identification of binding sites, whereas Fleck-seq captures the binding events in specific in vivo conditions. To test the contribution of shapes surrounding the motif, the amount of sequence, and therefore shape information, given to the regressor was varied and the training was repeated. The major contribution of shape information was localised to the core motif plus two bases on each side of the motif (Fig. 1c). These adjacent bases influence the shape of the bases and base pairs in the corevi. Beyond the core motif shape, the information gain quickly levelled (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Two additional machine learning approaches were evaluated and compared with RF performance (Supplementary Fig. ten). The baseline neural network implementation performed overall slightly worse than the slope boosting and random forest implementation. This relation would likely change with defended hyperparameter tuning. However, to be able to test the importance of the different Deoxyribonucleic acid shape features, we chose the RF-based machine learning approach to enable reliable feature extraction26.

The models generated past the shape-based regressor evidence which shapes are of import to the binding for each of 216 TFs tested equally shown in the source information file. To exam if any shape, shape blazon (intra-base of operations pair vs. inter-base of operations pair) or whatsoever position contribute a larger amount of information to the binding, the top five features were extracted for each TF. The 3D configuration of bases inside the core binding sequence occupied 68% of the top v characteristic positions (Supplementary Fig. xi) as expected (Fig. 1c). Intra-base pair shapes contributed 39% and inter-base pair shapes contributed 61% (Supplementary Fig. 11) of the summit v shapes within the core motif. Exterior of the motif, the proportions reversed since intra-base pair shapes contributed 72% and inter-base pair shapes contributed 28% (Supplementary Fig. eleven). Farther outside of the core motif, the shear feature was overrepresented among the peak five features (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Improved resolution of differential binding past transcription factor family members

If DNA shape predicts binding amend than the motif alone and shape information used by TFs is varied, the prediction algorithm should exist able to distinguish the binding between two TFs, which are predicted to bind the same motif sequence. To test this hypothesis, the models for TF pairs with the same sequence-only-based bounden motifs were analysed.

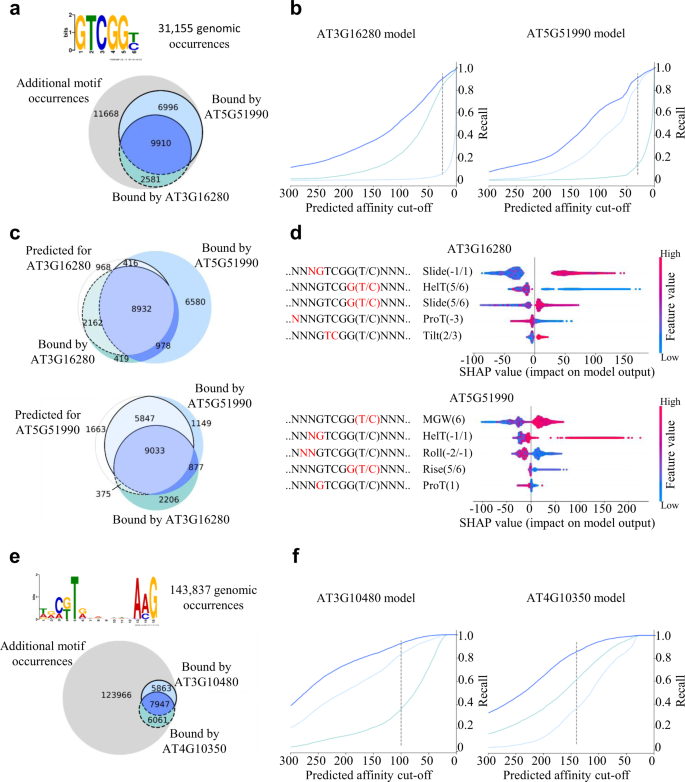

The ERF/AP2 TFs CBF4 (AT5G51990) and ERF036 (AT3G16280) both demark the GTCGGT/C motif which occurs 31,155 times in the A. thaliana genome. According to ampDAP-seq, both TFs accept 9910 binding sequences in common (Fig. 2a). ERF036 binds 2581 sequences which are non bound by CBF4, and CBF4 binds 6996 sequences not bound past ERF036. Using the published motif derived from the peak 600 binding events results in a smaller overlap but leads to 103,779 extracted genomic sequences (Supplementary Fig. 12). To examination whether the shape indeed encodes specificity, bounden vs. non-binding was predicted by the models (Fig. 2b).

a, e Occurrence of the GTCGG(T/C) and C(G/T)TNNNNNNNAAG binding motifs in the A. thaliana genome sequence and the experimentally validated binding sequences of the AP2/EREBP TFs AT5G51990 and AT3G16280 and NAC TFs ANAC050 (AT3G10480) and BRN2 (AT4G10350). b, f Performance of the random forest regressor trained on the genomic 3D shape. Each line represents the ratio of correctly predicted binding sites regarding all validated binding sites for different affinity prediction cut-offs. The night blue line corresponds to binding sequences which are bound by both TFs and the lite blueish lines correspond to the uniquely leap binding sequences. c The Venn diagrams prove the sequence distributions according to the cut-off represented by the dashed line, respectively. Fields with light colours prove the overlap of predicted and validated binding sequences. Dark coloured fields prove the quantity of sequences, which were not predicted equally bound by the model regarding the shown cut-off. d Influence of different local shape features on the prediction of the regressor model. The nearly influential features are at the elevation. Each row represents ane shape characteristic at a unmarried position within the sequence.

The shape information of the 31,155 genomic sequences, allows the regressor models to distinguish the bounden events between the two TFs (Fig. 2b, c), even though the core sequence is the same and the majority of sequences are jump by both TFs according to ampDAP-seq. Each Venn diagram in Fig. 2c shows the distribution of binding sites applying the cutting-off represented by the dashed line. For ERF036, 2162 out of the 2581 uniquely bound sequences were correctly identified as binding sequences, whereas only 416 out of the 6996 sequences bound uniquely by CBF4 were wrongly predicted equally binding sequences (Fig. 2c). In total, the number of false-positive bounden sequences from the motif search dropped from 18,664 (11,668 + 6996) to 1384 (968 + 416), which is an comeback of 93% less faux-positive predictions when using the RF model. Besides, for CBF4 84% of uniquely jump sequences were correctly predicted and only 15% of sequences bound uniquely by ERF036 are predicted every bit false positives (Fig. 2c). Here, the full improvement regarding imitation positives amounts to 86%, as the number of false-positive predictions dropped from 14,249 to 2038. To identify the features which contribute specificity to each TF, we extracted feature importances using 'shapley additive explanations' (SHAP)26 (Fig. 2d). The outputs of the regressor models are influenced by unlike features. For ERF036, the slide at position -1 relative to the motif and the helix twist at position 5 in the motif is most influential, whereas for CBF4 the minor groove width at position 6 and the helix twist at position −1 contribute near to the conclusion of the RF model. This observation underlines that the TFs, fifty-fifty though binding to the same core motif, are dependent on different peculiarities regarding the shape of the DNA (Fig. 2). These results are not family specific since TFs of the NAC family binding to the C(Thousand/T)TNNNNNNNAAG motif (Fig. 2e, f), TFs of the WRKY family binding to TTGAC(T/C) motif, TFs of the bZIP family unit binding to ACGTCA motif and TFs of the C2H2 family bounden to TTGCTNT motif show similar results (Supplementary Figs. xiii–15). In summary, the features defined past the shape-based regressor are able to explain differential binding of two TFs binding to the same sequence motif.

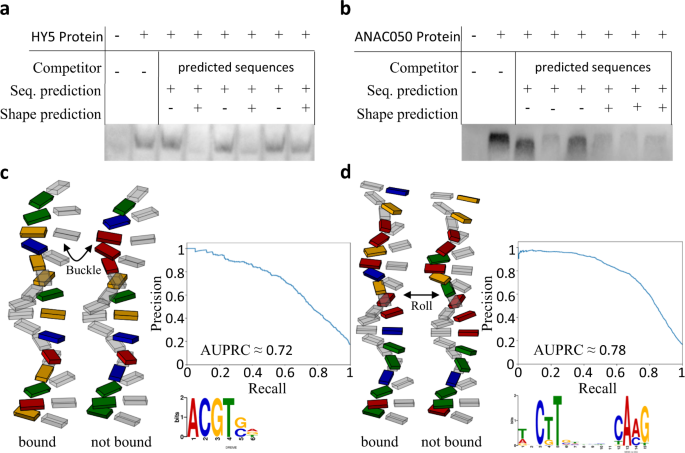

Binding affinity prediction on randomly generated sequences

The models generated past machine learning better bounden site prediction (Fig. ane) and distinguish bounden events for TFs binding the same motif (Fig. 2). To test if the models are able to produce novel data they were used to predict TF bounden to sequences non nowadays in the A. thaliana genome. For the HY5 (AT5G11260) TF of the bZIP family unit with the core motif ACGT, half dozen Dna sequences with high (>150 tiptop summit units) and low (<15 peak tiptop units) regressor binding predictions were generated. For this purpose, 100,000 sequences not present in the genome of A. thaliana consisting of 18 bases with ACGT as cadre sequence were randomly created and the regressor model was applied. Similarly, six Dna sequences were generated for the TF ANAC050 (AT3G10480). The predicted binding affinity was experimentally tested by performing an EMSA (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Figs. sixteen and 17). Without any competing unlabelled Dna added, a shifted band compared to the negative control indicates TF::Dna binding that is absent upon the add-on of unlabelled Deoxyribonucleic acid probe of the aforementioned sequence (Fig. 3a, b). In the comparative competition experiment with HY5, calculation competing DNA with shapes with low regressor values, all labelled bands are however visible (Fig. 3a). Those shapes are not able to out-compete the labelled sequence and are thus apparently not leap with high analogousness by HY5. For the shapes with loftier regressor values predicted to be bound, two out of iii practice not testify whatsoever labelled ring and are therefore bound by HY5 with sufficient affinity to out-compete the labelled sequence. For ANAC050 the EMSA shows similar results with 5 out of six predictions being right (Fig. 3b). In total, we observed that ten out of 12 predictions were experimentally validated for both TFs. Given that the AUPRCs for both proteins yielded 0.72 and 0.78 (Fig. 3c, d), the validation of binding and non-binding events occur within the expected error charge per unit. To illustrate the subtle relevant factors, schematic models of the Dna sequences were plotted. For HY5, the schematic model of base and base of operations pair shape shows clear differences on the buckle at position +3 and the shear of position −1 betwixt the bound and non jump sequences (Fig. 3c). Additionally, important positions for binding extracted with SHAP are the helix twist at positions 5 and +1 and the opening at position −ane. (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 18). For the ANAC050 protein, the most obvious difference betwixt the jump and not bound sequence is that the spring sequence is overall more stretched out. The primary reason for this observation is that the boilerplate roll for the bound sequence is approximately −0.88°, whereas the bases of the sequence which is not sufficiently bound are rolled on boilerplate by approximately −1.77° (Fig. 3d). The EMSA confirmed the predictive capability of the models constructed by automobile learning.

a, b Competition EMSA for sequences containing the sequence motif for each respective TF with high and depression binding affinity predictions based on their 3D structure. c, d Illustration of the 3D construction of the corresponding sequences. The DNA backbone is not shown, as it is not nonetheless possible to reliably calculate the spatial arrangement of the backbone. Additionally, the precision-recall curve of the RF models for the respective TFs are shown. Precision and recall are based on the ampDAP in vitro verified bounden sequences.

Discussion

Our results bear witness that the bounden behaviour of TFs depends on the 3D formation of its binding site, where different TFs favour dissimilar formations fifty-fifty within the same protein family. In dissimilarity to Flake-seq information, ampDAP-seq data, which uses naked genomic DNA4, allows a more precise identification of 3D feature importances for each TF individually. Large experimental efforts take been designed to precisely assign binding sites to TFs27 and to use this knowledge to describe transcriptional regulation28. Our analyses (Figs. 1–3) show that a combination of motif sequence and motif shape enables improved prediction of TF binding on genomic sequence. The models generate a catalogue of potential bounden sites in a genome and their predicted affinity. This data forms a base on which boosted information layers (i.east. spacing of bounden sites29, chromatin openness30, histone marksthirty, and quantity of TFs and their interactors) tin be stacked to enable prediction of gene expression. In synthetic biology, binding events for heterologously expressed TFs can exist predicted more precisely, and rationally designed promoter sequences are one step closer.

In the future, information technology will be critical to report evolutionary trajectories of transcriptional regulation to make up one's mind changes to binding sites present in genomes and changes to shape preferences of TFs. Precise agreement of TF bounden will permit us to build predictive regulatory networks and hence enable usa to sympathise agriculturally important circuitous traits, such as differential responses to oestrus, drought and pathogens and command of yield.

Methods

Data processing and extraction

The ampDAP-seq peak calling information were obtained from the Establish Cistrome Database (neomorph.salk.edu/dap_web/pages/index.php)4. Only datasets with a fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP) value >5% were considered for further analyses. All peak sequences were extracted from the A. thaliana reference genome sequence (TAIR10), obtained from https://www.arabidopsis.org/. The peak sequences were then used equally input for the MEME-ChIP tool31 to discover binding motifs. The motif with the lowest Due east-value was chosen every bit cadre motif for each TF. Peaks, which appeared in more than one-third of all datasets, are considered equally artefacts and were discarded.

To determine motif frequency in the genome, core motif occurrences were searched within the A. thaliana genome sequence using FIMO24. All motifs located within fourscore base pairs of a peak summit were considered every bit experimental validated binding events. Multiple motif occurrences within this divers meridian area were classified as homodimer bounden sites to enable a more precise signal value interpretation. The calculation of the Deoxyribonucleic acid shape was performed using a publicly available query table6,32 provided from https://rohslab.usc.edu/DNAshape+/.

The RF classifier equally well equally the RF regressor models were generated and trained using the python module scikit-acquire25. Hyperparameter grid search and 5-fold cross-validation were performed to generate each model. A more detailed explanation of the data pre-processing and model generation is provided in the subsection below. Lawmaking is available from GitHub (https://github.com/janiksielemann/shape-based-TF-binding-prediction). Required python packages are pandas33, numpy34, scikit-learn25, biopython35, matplotlib36, shap26, scipy37 and dabest38.

Pre-processing and training of the random forest regressor

To perform information pre-processing and training of a random forest model an ampDAP-seq peak file (from http://neomorph.salk.edu/dap_web/pages/browse_table_aj.php) and the A. thaliana genome (from arabidopsis.org) is necessary. Only peak files with FriP value >5% were considered and after motif extraction each peak file was filtered for peaks that announced in less than 66% of all ampDAP-seq available top files, as those peaks were considered artefacts due to the ampDAP-seq procedure. Peak regions were extracted from the Arabidopsis genome using a custom python script, which expects one superlative file (-p) and the corresponding genome (-g) as input. The resulting fasta file with genomic summit regions was used as input for the MEME-ChIP31 (MEME-suitetwenty v 5.0) tool with default parameters, so that the only given parameters were an output folder (-oc) and the peak regions fasta file (-deoxyribonucleic acid). The sequence motif with highest East-value (--motif one) from the resulting combined.meme file was searched in the A. thaliana genome using the FIMO24 (MEME-suite20 v 5.0) tool with a cut-off (--thresh) of 5e-4. To ensure that no matches were discarded the maximum number of stored matches --max-stored-scores) were gear up to i,000,000. The parameter --max-strand was set to 1 so that palindromic sequences would non match 2 times in the aforementioned locations and an output binder (--oc) was declared.

To allow a more than accurate interpretation of binding affinities, the areas of motif matches were scanned for multiple motif occurrences using a custom python script. For this, each height, which always has a length 200 base of operations pairs, was tested for multiple FIMO matches. If more peaks had multiple motif occurrences than single motif occurrences, the corresponding TF was considered for homodimeric binding events and vice versa. In that case, the random forest regressor was just trained on those peaks with multiple motif occurrences.

All genomic locations with sequence motif matches were translated into 13 DNA shape features using a publicly available query tablehalf-dozen, which was implemented into a custom Python script. Chloroplast and mitochondrial motif occurrences were discarded, as those sequences were non part of the in vitro experiment. Additionally, all sequences that were initially striking on the reverse strand were opposite complemented. The sequence window, for which the DNA shape was calculated, was set to 32 additional bases upstream and downstream from the sequence motif. Experimentally recorded signal values were normalised to range from 0 to 1000 using sklearn pre-processing module25. Since some shape features are mirrored for palindromic sequences, each matched sequence window on the minus strand was reverse complemented, and then that the matrix of 3D shape values e'er correspond to the same direction.

DNA shape-based training to learn protein binding affinities was performed with the RandomForestRegressor class from the sklearn module. The number of considered positions upstream and downstream of the sequence motif tin can exist specified using the custom Python script by setting the -b parameter, which has a default value of 4. If the ratio of experimentally verified binding sites and genomic binding site occurrences was too high (>i:5), this ratio was forced to be 1–v by discarding random genomic positions. If this process would still yield more than 120,000 locations, the ratio was forced to be 1–3. This ratio between validated binding sites and binding site occurrences was always calculated for each TF and used as sample weight for training the random woods regressor to prevent bias towards false negatives. The whole dataset was divide into a train set (eighty%) and a validation gear up (20%) using the train_test_split function provided by the sklearn module, applying stratification to ensure fifty-fifty distributions of validated bounden sites in the train and test set. The railroad train prepare was used for five-fold cross-validation learning and the validation set was used for evaluation. Within the 5-fold cross-validation, the train set was dissever into train and test set with a ratio of iv:1. The model was then trained v times and so that each case was function of the test ready in one case. To finetune the learning process, randomised hyperparameter grid search was performed for 75 iterations including the parameters "n-estimators" (ranging from 10 to 200), "max_features" (auto, foursquare root or log2) and "max_depth" (ranging from 4 to 12). As each of the 75 iterations for hyperparameter tuning was five-fold cross-validated as described, a total number of 375 training procedures for each respective TF was performed. The hateful squared mistake was used every bit loss. For evaluation purposes the precision recall curve function, which is too provided by the sklearn module, was applied on the validation data. The validation information was not used for hyperparameter tuning but solely for evaluation, as it was separated from the train data within pre-processing. After training the model, sequences of involvement can be checked for putative bounden analogousness.

Training of other baseline models

To perform the comparative analysis between machine learning approaches we trained gradient boosting models and neural networks for each TF, respectively. The pre-processing steps were the same for each approach, so that each approach had the same input dataset.

For the gradient boosting approach nosotros used the "GradientBoostingRegressor" class from the sklearn python packet. Likewise setting a random state, the default parameters were used for the baseline model.

To build the neural network model, the "Sequential" form from the keras API was used. The input shape was defined according to the number of input features for the corresponding TF, as the length of the core motif differed from poly peptide to protein. A dense layer with 200 neurons and ReLU every bit activation function was added, as well as an output layer to predict the signal value. The model was compiled, defining the mean squared fault equally loss and keras "Adam" course every bit optimiser with a learning rate of 0.001.

Example application based on the transcription factor HY5

For the TF HY5, the peak calling of the in vitro ampDAP-seq experiment identified 10,140 DNA-binding sites (Fig. 1a). Those binding sites were used to summate the sequence motif using MEME-Chip31. Nosotros referred to the resulting sequence motif as "core motif", as we took additional bases upstream and downstream from the motif to convert the sequence into shape features as described. Using this sequence motif of HY5 to extract all genomic sequences that contain the motif yields 55,740 genomic sequences (Fig. 1a). The mitochondrion, as well as the chloroplast were not considered.

The extracted 55,740 potential HY5 binding sequences were converted to Dna shape features6. In the instance of HY5, 4 bases upstream and downstream of the core motif were incorporated to convert the sequence into shape features. As shown in the illustration, additional pre-processing steps like the calculation of the sample weights were conducted. All samples were labelled co-ordinate to the measured point value inside the top calling of the ampDAP-seq experiment to enable the regression task.

A validation set which contained 20% of the dataset was separated to ensure an independent evaluation. This dataset was non used for hyperparameter tuning. The random woods regression model was trained on the remaining fourscore% of the dataset, which was again dissever into train and test fix within the 5-fold cantankerous-validation procedure (Fig. 1a). For hyperparameter tuning a grid search was performed. The best performing model for HY5 ended up with the parameters of 'n_estimators' = 190, 'max_features' = 'sqrt' and 'max_depth' = 11. This model was used to predict the signal values of the samples in the validation set and the performance was evaluated past computing a precision recall curve.

Experimental procedure

The HY5 (AT5G11260) and ANAC50 (AT3G10480) coding sequences were cloned with Gibson assembly in pFN19A HaloTag® T7 SP6 Flexi® Vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA; Cat.: G921A; Batch: 0000341144; 1:10,000) in an N-terminal fusion with the Halo-tag. Plasmid DNA was isolated with the ZymoPURE Plasmid Midiprep kit (ZymoGenetics, Seattle, WA, Usa). The HY5 protein was expressed with TnT® SP6 High-Yield Wheat Germ Poly peptide Expression System (Promega, Madison, WI, Usa) using 2 µg plasmid Deoxyribonucleic acid per 50 µL expression reaction. The ANAC050 protein was purified with the HaloTag® Protein Purification System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) using 20 µL expression reaction for each EMSA reaction. Expression was validated by Halo-tag detection (Supplementary Fig. 14). Double-stranded Dna sequences (20 µM) were generated by annealing synthesised Dna (98–21 °C, ix h) and diluted to 0.25 µM. The binding reaction was incubated for ii h at 21 °C. A 5% native polyacrylamide gel containing 0.v TBE and two.five% glycerol was pre-run for thirty min. The samples were loaded with i µL orange loading dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and the gel (ten × seven.five cm) was run at 80 V until the OrangeG front was 1 cm earlier the stop of the gel. The gel was blotted on a positively charged nylon membrane (HybondTM, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) at fixed current of 0.viii mA/cm2 for 90 min. The Dna was fixed by UV for 10 min. Biotin labelled Dna was detected with 1:5000 solution of an anti-biotin HRP-conjugated antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA; True cat.: 405210; Batch: B293545; 1:5000) in TBST with 5% BSA. Detection was performed using PierceTM ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, Usa) as described by the manufacturer and the imaging system Fusion Fx7 (Vilber, Collégien, France).

Reporting summary

Further data on research blueprint is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this commodity.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this newspaper, containing the sequences used for the EMSA, uncropped gel images and resulting values, which were used to create the figures. To translate Dna sequence into shape features, the publicly available query table (https://rohslab.usc.edu/DNAshape+/) was used6. The ampDAP-seq peak calling data, which were used equally ground truth to train the models, were obtained from the Plant Cistrome Database (neomorph.salk.edu/dap_web/pages/alphabetize.php). Source data are provided with this newspaper.

Code availability

The lawmaking to train a model and predict binding affinities for a given transcription factor is available from GitHub (https://github.com/janiksielemann/shape-based-TF-bounden-prediction)39.

References

-

Riechmann, J. Fifty. et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 290, 2105–2110 (2000).

-

Bowman, J. L. et al. Insights into state plant evolution garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha genome. Cell 171, 287–304.e15 (2017).

-

Bailey-Serres, J., Parker, J. Due east., Ainsworth, Due east. A., Oldroyd, K. Eastward. D. & Schroeder, J. I. Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature 575, 109–118 (2019).

-

O'Malley, R. C. et al. Cistrome and epicistrome features shape the regulatory Deoxyribonucleic acid landscape. Prison cell 165, 1280–1292 (2016).

-

Fornes, O. et al. JASPAR 2020: update of the open-admission database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D87–D92 (2020).

-

Li, J. et al. Expanding the repertoire of DNA shape features for genome-scale studies of transcription factor bounden. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 12877–12887 (2017).

-

Chiu, T.-P., Xin, B., Markarian, N., Wang, Y. & Rohs, R. TFBSshape: an expanded motif database for DNA shape features of transcription gene binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D246–D255 (2020).

-

Rohs, R. et al. The part of Dna shape in poly peptide–DNA recognition. Nature 461, 1248–1253 (2009).

-

Abe, N. et al. Deconvolving the recognition of DNA shape from sequence. Cell 161, 307–318 (2015).

-

Gordân, R. et al. Genomic regions flanking Eastward-box binding sites influence Deoxyribonucleic acid binding specificity of bHLH transcription factors through DNA shape. Prison cell Rep. 3, 1093–1104 (2013).

-

Rushton, P. J., Somssich, I. E., Ringler, P. & Shen, Q. J. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Establish Sci. 15, 247–258 (2010).

-

Ülker, B. & Somssich, I. E. WRKY transcription factors: from Deoxyribonucleic acid binding towards biological role. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7, 491–498 (2004).

-

Ciolkowski, I., Wanke, D., Birkenbihl, R. P. & Somssich, I. E. Studies on DNA-binding selectivity of WRKY transcription factors lend structural clues into WRKY-domain function. Plant Mol. Biol. 68, 81–92 (2008).

-

Heim, M. A. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in plants: a genome-wide study of protein structure and functional diverseness. Mol. Biol. Development 20, 735–747 (2003).

-

Foster, R., Izawa, T. & Chua, N. Plant bZIP proteins gather at ACGT elements. FASEB J. 8, 192–200 (1994).

-

Jakoby, G. et al. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 106–111 (2002).

-

Chow, C.-N. et al. PlantPAN3.0: a new and updated resource for reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks from Flake-seq experiments in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1155–D1163 (2019).

-

Burko, Y. et al. Chimeric activators and repressors define HY5 activity and reveal a light-regulated feedback mechanism. Establish Cell 32, 967–983 (2020).

-

Birkenbihl, R. P., Kracher, B., Roccaro, M. & Somssich, I. E. Induced genome-wide binding of three Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factors during early MAMP-triggered immunity. Constitute Cell 29, 20–38 (2017).

-

Bailey, T. Fifty. et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208 (2009).

-

Yu, C.-P. et al. Transcriptome dynamics of developing maize leaves and genomewide prediction of cis elements and their cognate transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. United states of america 112, E2477–E2486 (2015).

-

Gao, F. et al. Blocking miR396 increases rice yield by shaping inflorescence architecture. Nat. Plants 2, 15196 (2016).

-

Dror, I., Golan, T., Levy, C., Rohs, R. & Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. A widespread role of the motif environment in transcription gene binding across diverse protein families. Genome Res. 25, 1268–1280 (2015).

-

Grant, C. E., Bailey, T. L. & Noble, W. South. FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27, 1017–1018 (2011).

-

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: automobile learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

-

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

-

Ambrosini, 1000. et al. Insights gained from a comprehensive all-against-all transcription gene binding motif benchmarking written report. Genome Biol. 21, 114 (2020).

-

Alipanahi, B., Delong, A., Weirauch, M. T. & Frey, B. J. Predicting the sequence specificities of Deoxyribonucleic acid- and RNA-bounden proteins by deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 831–838 (2015).

-

Freire-Rios, A. et al. Architecture of DNA elements mediating ARF transcription factor binding and auxin-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24557–24566 (2020).

-

Lu, Z. et al. The prevalence, evolution and chromatin signatures of constitute regulatory elements. Nat. Plants 5, 1250–1259 (2019).

-

Machanick, P. & Bailey, T. Fifty. MEME-Bit: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics 27, 1696–1697 (2011).

-

Chiu, T.-P. et al. DNAshapeR: an R/Bioconductor parcel for Deoxyribonucleic acid shape prediction and characteristic encoding. Bioinformatics 32, 1211–1213 (2016).

-

McKinney, W. Information structures for statistical computing in Python. In Proc. of the 9th Python in Science Briefing. (Editors: van der Walt, South. & Millman, J.) 56–61 (2010).

-

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

-

Cock, P. J. A. et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 25, 1422–1423 (2009).

-

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2nd graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, ninety–95 (2007).

-

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy i.0: primal algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

-

Ho, J., Tumkaya, T., Aryal, S., Choi, H. & Claridge-Chang, A. Moving across P values: data assay with estimation graphics. Nat. Methods 16, 565–566 (2019).

-

Sielemann, J. janiksielemann/shape-based-TF-binding-prediction: first release. zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.5559534. (2021).

Acknowledgements

Nosotros thank the Bioinformatic Resource Facility squad at the Eye for Biotechnology (Bielefeld University) for technical support. J.S. is funded by the Digital Infrastructure in the Life Sciences graduate school (Bielefeld Academy). D.W. is supported past core funding, Bielefeld Academy.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. designed and carried out the computational experiments including programming, interpreted the data and co-wrote the paper. D.W. designed and carried out the wet lab experiments, interpreted information and edited the paper. R.S. assisted with the wet lab experiments, interpreted data and edited the paper. A.B. conceived the initial idea and the study, interpreted information and co-wrote the paper.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review data Nature Communications thanks Xiangfeng Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this piece of work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher'due south notation Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give advisable credit to the original writer(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If fabric is non included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended utilize is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, you volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this commodity

Sielemann, J., Wulf, D., Schmidt, R. et al. Local Dna shape is a general principle of transcription factor binding specificity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun 12, 6549 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26819-2

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41467-021-26819-2

Comments

Past submitting a comment you agree to bide by our Terms and Customs Guidelines. If yous detect something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it every bit inappropriate.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-26819-2

0 Response to "Specificity of Transcription Factor Binding Sites Matrix Families"

Post a Comment